Learning in the time of Corona: Tips for Teaching English Remotely (Part 3)

Are my students writing regularly?

Consideration #1: Keeping it Real: Relevance and Meaning

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.jpg

A teacher friend from overseas received this advice when she first dipped her toes into the remote learning ‘pool’: “Plan for one week. Then halve it. That’s more than realistic for right now.” With a similar focus on ‘the realistic’, my last two posts on reading and meaningful interaction stressed that whatever we do right now needs to be meaningful and sustainable – for our students and for ourselves—especially when a lot of us are feeling ‘end of term tired’ as we work harder than ever.

That’s why I’ve decided to centre Part 3 of this post on teaching English remotely around one single question:

“Are my students writing regularly?”

Why this question? Author Jane Yolen puts it best, with this gem:

“Exercise the writing muscle every day, even if it is only a letter, notes, a title list, a character sketch, a journal entry. Writers are like dancers, like athletes. Without that exercise, the muscles seize up.”

When teaching remotely, I know I’ll need to approach some aspects of English teaching with more flexibility, but I still want to ensure that students are writing regularly in some way. Why? Research tells us that writing volume matters and is acknowledged as a “necessity” for full participation in society (Graham and Perin, 2007: 3). And as some of my Year 10s once put it during a class brainstorm, it helps us:

express feelings

give voice to our opinions

explore thoughts

explain information

argue a point

make sense of what’s confusing

dream up solutions

learn new things

In other words, it helps us ‘talk back’ to our world and find a place in it.

So how might we nurture this under remote learning conditions? Here are two ‘umbrella’ considerations I’ll cover; the first one in this post, and the next one in an upcoming post at the end of the week:

1. Keeping it real: Relevance and meaning

2. Models, mentors, process

Because there’s so much to say about feedback, I’ll be addressing that topic in an upcoming post rather than here.

Keeping it real: Relevance and Meaning

At a time when many of us feel like we’re ‘building the plane as we’re flying it’, we might feel tempted to assign writing like we normally would . But now, more than ever, is a time when our students need relevant and meaningful writing experiences, and what might have been relevant and meaningful under normal circumstances might not be so in this current climate. I’m not suggesting a complete reinvent of the wheel here. Rather, I’m suggesting we let go of the pressure to do everything, figure out what’s really essential for students’ learning and create invitations and opportunities for students to connect to and explore it through writing.

So…what could this look like? While I won’t presume to know what is currently relevant and meaningful for your students, what I will do is outline some possibilities as food for thought:

Relevance to the writer: The power of choice

When we ask students ‘why are you writing this?’ or ‘why did you make this writing choice?’, the last thing we want to hear is “because I have to” or “because I was told to.” For writing to be truly meaningful and not just another item to tick off a to-do list, it makes sense to offer students choices when it comes to their writing. Here are a few approaches to think about in terms of the current teaching and learning context:

Finding ideas to write about:

Simply giving students free rein to select ideas to write about might be great for some, but we know that most students need more structure, support and scaffolding to help generate writing ideas. Modelling and showing students how to use idea generation strategies like listing, prewriting and low-stakes writing (informal, quick, non-graded writing) can help with this. If you click on the image below, you’ll find a Google slide with hyperlinks to activities like this that are designed to help students generate ideas for:

personal narrative writing

imaginative writing

poetry

persuasive writing

informative writing

analysis of argument

responding to texts in writing

comparative writing

If you click on one of the hyperlinks (eg: Personal Narrative, Poetry, Responding to Reading, etc.) you will be transported to a resource containing prewriting activities.

Some other idea-generation strategies are explored below:

Writing Territories:

As outlined by Nancie Atwell (2002), students can make a list of ‘writing territories’ – a writing “ideas bank” of topics they’d like to write about, what they’d like to try as writers, genres they’d like to write in and possible audiences and purposes. When students are not sure what to write about, they can dip into this list and use it as inspiration for a piece of writing. The teacher can show students how to select an idea from a writing territories list and start planning for a larger piece of writing in any genre. Writing territories can include: memories, passions, places, people, dreams, fears, problems, hobbies, achievements, wonderings, songs, movies, favourites (songs, artists, musicians, books, foods, etc.), sports, rituals, holidays, confusions –anything!

See an example of my writing territories list below which is designed to share with a junior English class, created using Google Jamboard:

Top Ten Lists

Similar to the writing territories list, this strategy encourages students to make a ‘Top 10’ list of things they know a lot about and are interested in. This could be a general ‘Top Ten List’ to generate ideas for writing, a ‘Top Ten List’ in relation to a text that students are reading, or it could even be about things they’d like to change in the world for persuasive writing. Students can then select an item from the list and write about it. They might: use the five senses to describe it, jot down their thoughts and feelings about it, write down ‘wonderings’ or questions or apply it to a particular genre they are exploring. This strategy is outlined by Kelly Gallagher in his book Write Like This. See an example of a general ‘Top Ten List’ below:

Genre and form-based choices:

Students can also be given choices regarding the genres and forms they are writing in. One way of doing this is to create choice boards or ‘writing menus’ with models of different forms of writing within a particular genre. Students can then choose which form to write in, followed by either viewing an instructional video on writing in their chosen form, a written worked example or can engage in small-group videoconferencing about it.

The image below shows an example of a choice board: - click on it to be transported to a Google Doc with hyperlinked supporting documents:

Partial choice:

In his 2006 book Teaching Adolescent Writers, Kelly Gallagher discusses designing writing assignments that allow for partial student choice as a way of working students into “required writing discourses”. Some possibilities here might include:

o choosing an issue they care about as a subject for a persuasive piece

o designing their own question to respond to a text they have read

o designing an inquiry question that will drive the research and writing of an informative blog post

o Choosing from a list of writing options or possibilities

Relevance to the current moment: personal writing experiences

If you’re looking for an approach to writing that is relevant to the current moment, facilitates student choice, agency and voice and can help students make sense of the world they are living in, then you might consider personal narrative or ‘living through history’ writing.

This could include:

Sustained daily reflective writing in a notebook to capturing thoughts, questions, comments and concerns. See our QuickWrites of the Day and Kelly Gallagher’s ‘Coronavirus Lesson Plan’ as an example.

Letters to loved ones or friends that students have not seen in a while

Letters to a country or object, or past version of oneself. See this example from Italian novelist Francesca Melandri, ‘Letter to the UK from Italy: This is what we know about your future’

Letters to Coronavirus itself! See this example from poet Lucky Samuel Man'gera.

Poetry about this moment. To access a slide deck with some examples of poetry, click here.

Creating a journal as a ‘primary source’ for future historians (see this post for a description and some guiding questions from Middleweb)

Short, sharp daily writing. For inspiration, check out the ‘QuickWrite of the Day’ blog posts and slide deck on this site.

Sharing uplifting, thoughtful or hopeful stories with images, Humans of New York-style

Responding in writing to relevant news articles about this moment we are living in – The New York Times has placed all of these stories for a student audience in one place. To access, click here. You could ask students what they notice, think, feel, wonder or are puzzled by in relation to the articles, and encourage them to explore their questions.

What to do with these pieces of writing? You could create anthologies that can be ‘launched’, celebrated or turned into e-books, write a collaborative class poem (1-2 lines each) about what life has been like at the moment and share via Google Classroom or email, or give ‘gifts’ of writing to family members or friends (letters are a good choice for this).

You could ‘gather’ short pieces of writing on Google Slides, Google Docs, Padlet or Flipgrid and encourage students to give ‘I noticed…/I liked…’ feedback to each other. There are lots of possibilities here!

Relevance to what they are currently learning: Using writing as a tool for deeper thinking

Alternatively, you might be thinking about ways your students can use informal writing as a tool for thinking and learning. In this case, the goal of writing would not be publication or assessment, but for students to express and explore their thinking about the content they are studying.

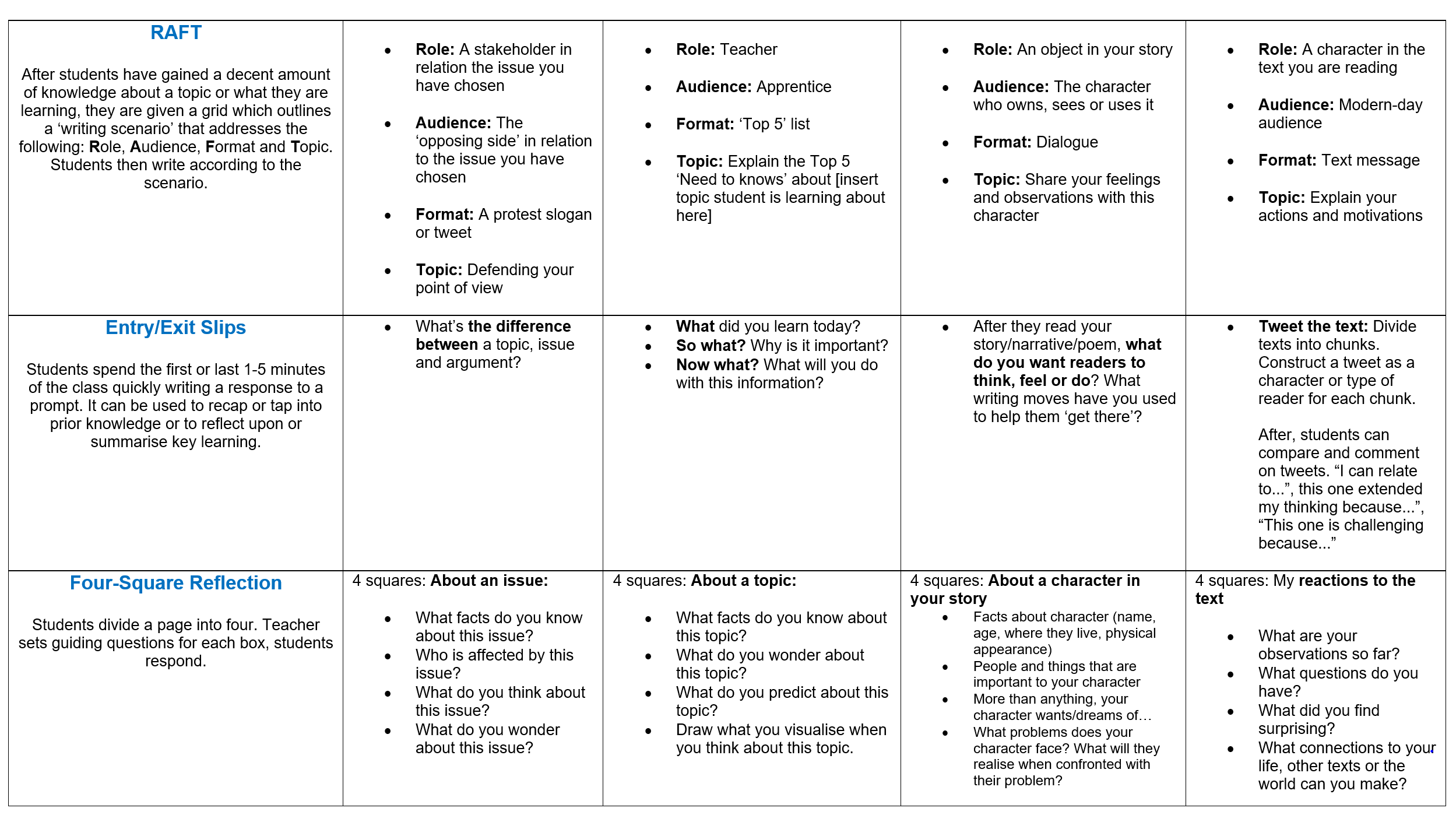

The table below contains some examples of writing strategies that might be used in English to get students to ‘put pen to paper’ and explore their thinking. Students can either jot these down/type responses individually and share them privately with you via email or Google Classroom. Alternatively, they could write/type their responses onto a collaborative space like Padlet, Flipgrid, Google Doc or Google Slide.

In the table below, the types of writing students might be working on are featured in red, whereas the strategies are featured in blue.

For writing strategies and approaches relevant to particular genres and for writing strategies at the word and sentence-level, check out the Victorian Department of Education’s Literacy Toolkit here and here respectively.

Relevance to their readership: real audiences and purposes

Often, the best motivator for writing is knowing that you are writing for real audience or purpose. In our current conditions, some examples might include:

‘How to’ procedural texts intended for their classmates at this time, who might want to learn how to do something new

Writing a persuasive letter to a business or government representative about a current issue

Informative blog intended for an audience of younger students learning about a particular topic

‘Gifts’ of reflective writing for loved ones: moments of hope, best memories, etc.

Additionally, if students are looking for a readership beyond their classroom, they can enter some writing competitions. A few are listed below:

Some writing Competitions:

· VATE Strange Stories for Strange Times writing competition (Entries due Monday 1st June)

· Red Room Poetry and Copyright Agency’s ‘Poetry Object’ competition (submissions close 22nd May 2020)

· Arts Learning Festival Student Poetry Competition 2020 (Entries due 22nd May 2020)

· The Dorothea Mackellar Poetry Award (Entries close 30th June)

In closing, here are some of the key take-aways from this post. Stay tuned for the final post in this four-part series, which will address writing models, mentors and process:

In what ways are you approaching the teaching of writing in this context?

References:

Atwell, N (2014). In the Middle: A Lifetime of Learning about Adolescents, Reading and Writing, 3rd Edition. Heinemann, Portsmouth: NH.

Daniels, H., Zemelman, S. & Steineke (2007). Content-Area Writing, Heinemann, Portsmouth: NH.

Gallagher, K (2006). Teaching Adolescent Writers. Stenhouse, Portland: ME.

Gallagher, K. (2011). Write Like This. Stenhouse, Portland: ME.

Graham,S & Perin, D (2004). Writing Next: Effective Strategies to Improve Writing of Adolescents in Middle and High Schools, Carnegie Corporation: New York, NY.

Peery, A., (2009). Writing matters in every classroom. The Leadership and Learning Center, Engelwood: CO.

Ritchhart, R.,Church, M. & Morrison, K. (2011). Making Thinking Visible. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA.