From ‘I don’t know’ to ‘I’m thinking’: Helping students respond to open-ended questions about reading when they don’t know where to start

By Nicole Marie and Judy Douglas

Some of us have experienced situations where we’ve asked students open-ended questions about their reading, like “What do you think?”, “What did you notice?” and “What struck you most?”, and have heard crickets as a result, even after we’ve given students opportunities to brainstorm and talk about it. In some cases, we might even see students write “I don’t know”, or its dreaded cousin “idk”. Looking around the classroom in this kind of scenario, it might appear as if students have ‘checked out’, or perhaps their working memories have become overloaded.

In situations like this, it can be quite tempting to revert to closed questions, or to rescue students by doing a lot of the thinking for them — “to get them started”, we tell ourselves. The danger here is that students quickly learn that if they struggle to think of something to write immediately, that the teacher will jump in and fill that space for them with their thinking, which is the opposite of what we’re trying to achieve by asking rich, open-ended questions about texts that invite interpretation! So what’s a good teacher to do?

Today’s post addresses this common dilemma, and offers some ways in which we can be more focused and explicit when inviting students to respond to their reading in situations like the one described above. At no point are we suggesting that we ditch open-ended questioning from our ‘teaching toolkits.’ Instead, we’re suggesting that when initially, it doesn’t seem to elicit thoughtful student responses, we can begin with more specific starting points that will eventually connect to a ‘bigger-picture’, to support students to move from ‘idk’ to “I’m thinking…”.

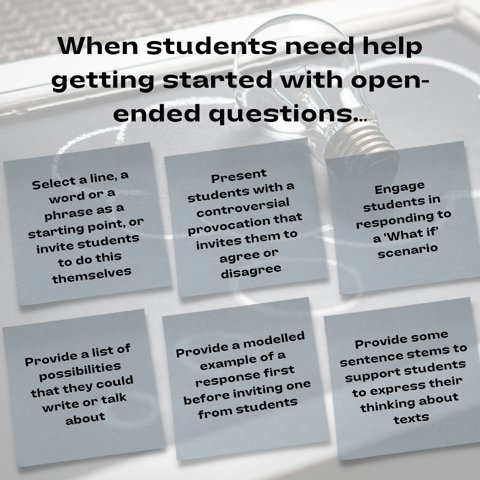

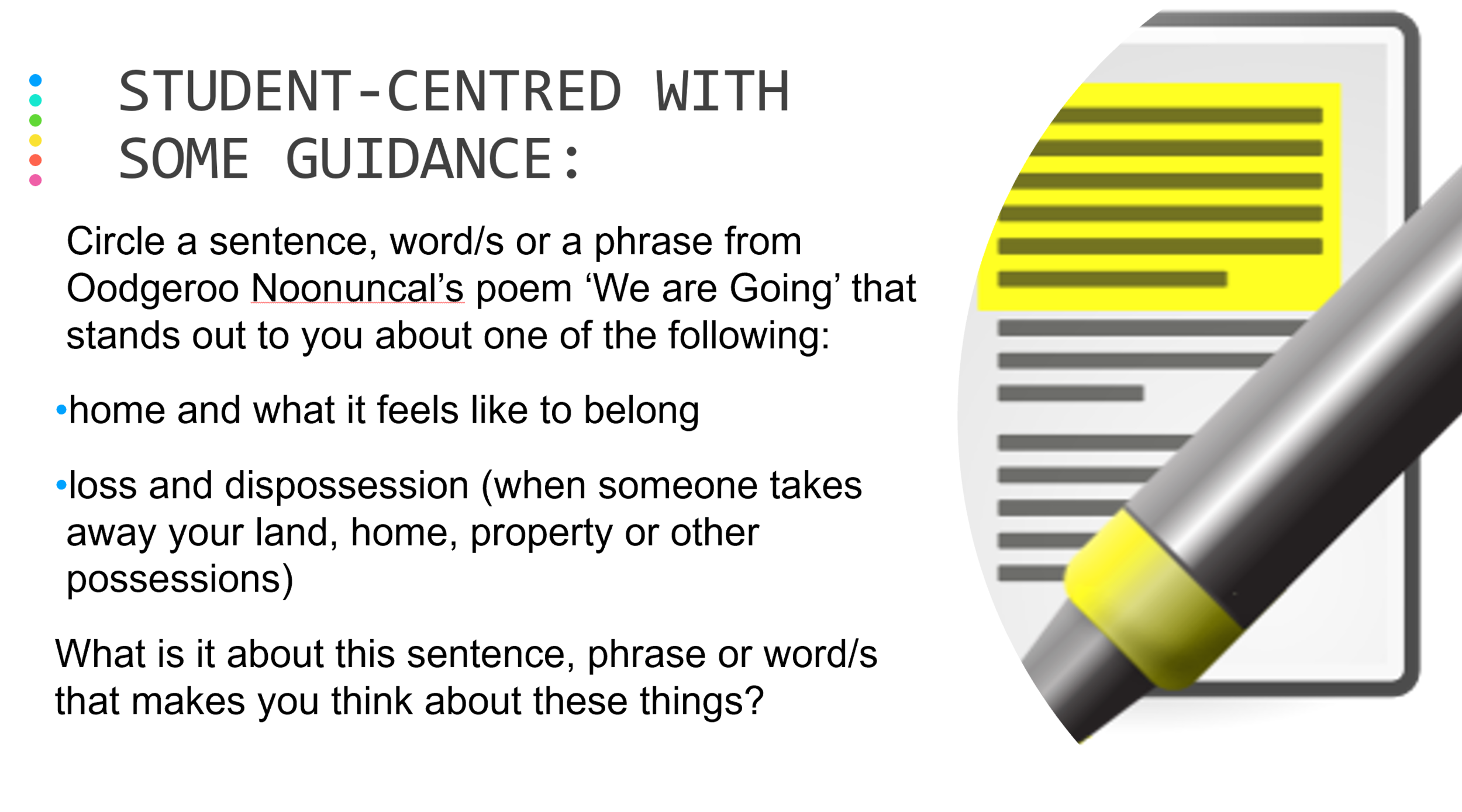

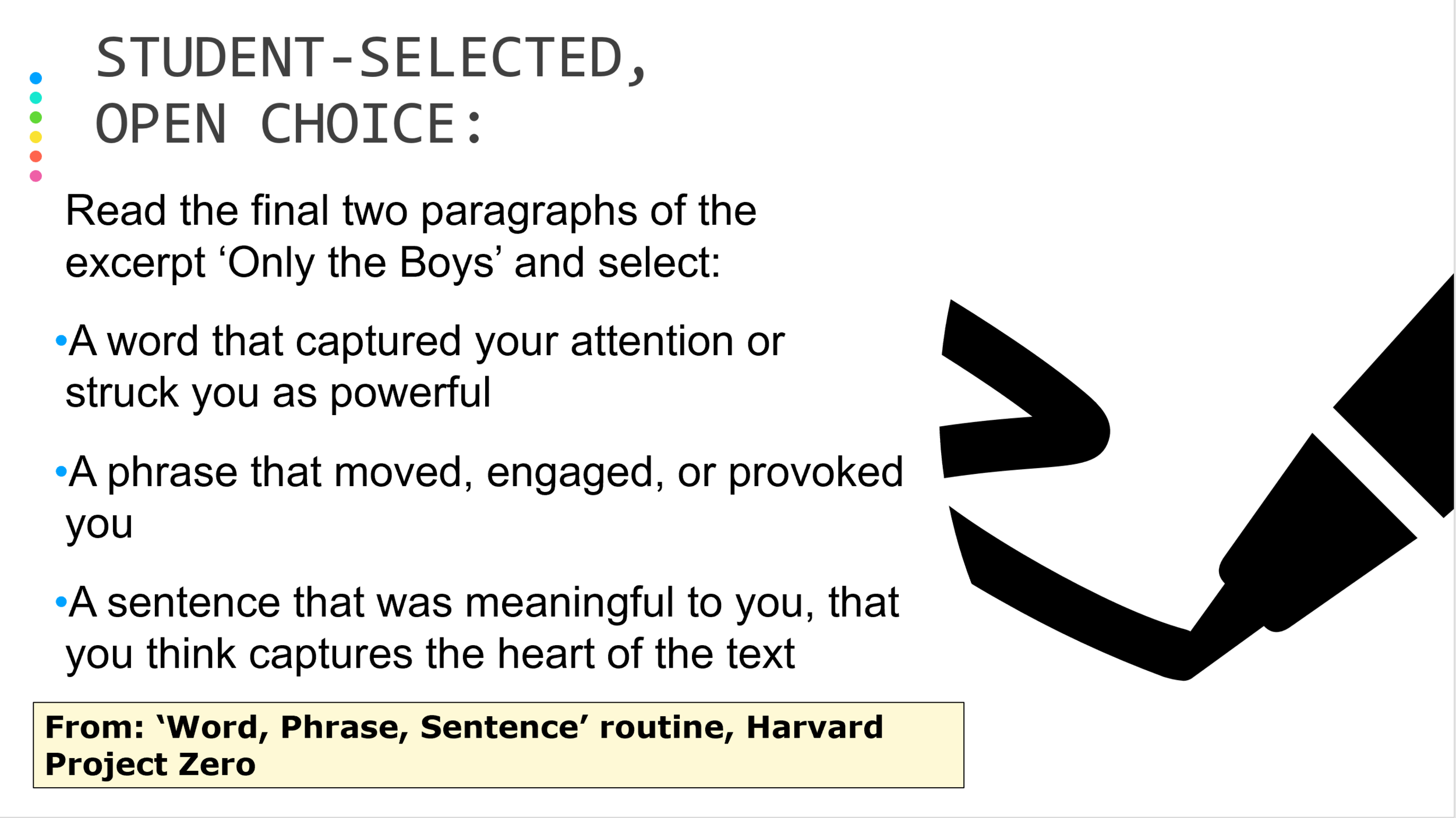

1. Select a line, a word or a phrase as a starting point, or invite students to do this themselves

See the examples of prompts like these in the slideshow below, which consist of an assortment of teacher-selected, guided and student-selected examples:

2. Present students with a controversial provocation that invites them to agree or disagree

3. Engage students in responding to a ‘What if’ scenario

These often involve questions around ‘word replacement’ or replacement of literary features or structural elements of texts (eg: “What if the story ended like…instead of…“, etc.). Here are some examples:

What if the character found out about ______ earlier? Do you think things would have been different? Why/why not?

What if Elizabeth Bishop had not included the phrase “(Write it!)” in the last line of the poem ‘One Art’? Would your ideas about the poem and its meaning be different? How?

4. Provide a list of possibilities that they could write or talk about

See some examples below:

An example of some prompts used for scene analysis, to support a ‘See, Think, Wonder’ thinking routine (Harvard Project Zero - available here)

An example of some starting points offered to students to help them analysing the significance of the title of the text

5. Provide a modelled example of a response first before inviting one from students

This might take the form of a ‘think aloud in passing’, like “Looking at this passage, I’m thinking I might write about…”.

Alternatively, it could involve a fully written modelled response like the ‘Lift a Line’ response below:

A modelled ‘Lift a Line’ personal response

6. Provide some sentence stems to support students to express their thinking about text

This involves providing students with some ‘language tools’ to get them started when expressing their thinking about the text. See the example below:

Some sentence stems to support student writing in a double-entry journal

Some sentence stems to support students’ writing analysis of language choices in texts

Finally, below, you’ll find a graphic that summarises of some of the six options we explored today. What do you do to support students to engage with open-ended questions about texts?