Learning in the time of Corona: Tips for Teaching English Remotely (Part 1)

Part 1: Are my students reading regularly?

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.jpg

It’s a strange time to be starting a blog, given the rapid changes that have recently swept the world in the midst of this global pandemic. But before “social distancing” and “#flattenthecurve” became part of our everyday vernacular (and our lives!), ‘The Literacy Village’ was under construction, and we believe that now, more than ever, is a time to reach out to each other and strengthen community.

As educators, we find ourselves in a situation where we’ve had to adapt to new circumstances and adjust what we’re doing very quickly. With that, has come a general sense of overwhelm and uncertainty amongst teachers and students. Parents are feeling it too, if the flood of “teachers should be paid a million dollars” social media posts are anything to go by!

At a time when a lot of us are feeling like pre-service teachers again, it’s important to give ourselves permission to pause for a moment, take a breath, and think about what matters most when it comes to our students’ learning right now. Or, as Narissa Leung in her Oz Lit Teacher blog post puts it, “we need to focus on what is reasonable, purposeful and sustainable” when it comes to teaching and learning during school closures.

Putting my English teacher ‘hat’ on, this means setting realistic expectations and encouraging meaningful learning and connection in the clearest way I can at the moment. In the spirit of keeping it simple, I’ll be asking myself three fundamental questions:

1. Are students reading regularly?

2. Are students writing regularly?

3. Do my students have opportunities to interact purposefully with others?

I’ll be addressing each of the above questions in a separate blog post, starting with #1: ‘Are students reading regularly?’

For Clarity’s Sake: Some Initial Considerations for Approaching Remote Learning

Before I launch into the above question, I’d like to point out that while the main focus of these posts will be on student learning (as it always should be!), some online learning tools will also be referred to throughout. A word of caution, though: when approaching online learning tools and websites, it can be tempting to sign up for all the shiny new things at once. For the sake of clarity and your sanity, resist! What we already know about quality teaching and learning shouldn’t be discarded just because we’ll be interacting remotely. Instead, consider how both the online and ‘offline’ learning tools you are considering will reflect the foundations and routines of your in-person classroom, and how they will:

Help students recap and review what they have learnt

Provide clear scaffolds and supports for student learning

Enable checks for understanding and feedback

No teacher wants to be spending their precious remote teaching time tinkering with complicated tools that are not absolutely crucial to learning!

Another thing: instead of sending students home overloaded with documents and links in different places, it’d be worth setting up a basic online platform (if you don’t already have one) to assign and collect work on a weekly basis, and communicate with students and carers how you will use it. On your platform, you could post a simple ‘What’s in Store This Week’ document that houses all the work students will engage in throughout a week. For students without internet access, you can send hard copies home or take a photo and send to a parent or carer’s phone. That way, you, students and their carers can use it as an ‘anchor document’ to help with planning, establishing routines and adjustments to learning. To see an example of one shared on Middleweb by international teacher Tan Huynh from Empowering ELLs, click here.

Finally, to ensure quick communication with parents and carers across language barriers, the Talking Points app can be used to send free SMS messages from a web browser or mobile to families in English, which will then translate into their home language. Parents or carers can respond to the teacher by texting in their home language, and the message will then be translated into English for the teacher to see.

Now…let’s talk about reading!

Are students reading regularly?

“A child who reads abundantly develops greater reading skills, a larger vocabulary, and more general knowledge about the world. In return the child has increased reading comprehension and therefore, enjoys more pleasurable reading experiences and is encouraged to read even more.” (Cunningham, 2005: 63)

If there is one simple thing that can enrich students’ learning during this time (or at any time!), this is it. Numerous studies highlight the relationship between the volume of students’ reading and their reading achievement.[i]And let’s not forget about the therapeutic benefits of reading–there’s a reason why books were prescribed to WWI soldiers returning from the front!

So, what can be done about this in a remote learning environment? There are a few things to consider here, which I’ll detail under the headings below.

Please note that these considerations are presented as a ‘buffet’ of potential options to carefully think about. Use what you know about your students and your learning purpose as a ‘filter’ –which one or two things would be most meaningful and purposeful for your students at this time?

Reading Consideration #1: Access to texts

“The job of adults who care about reading is to move heaven and earth to put [the right] book into a child’s hands” (Atwell, 2007: 27—28).

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Access to books:

Some students will already have access to texts, but we know that this won’t be the case for everyone. Aside from sending reading materials home and encouraging students to load up on books before remote learning periods begin, the apps below can provide free access to books and can be accessed via phone and computer. You can encourage students to self-select a book (or several) to read over the course of a week or set period of time:

Borrowbox: This Australian app enables students to use their existing local library card to borrow audio and e-books.

Get Epic: Access to a comprehensive digital library of children's books (picture story books and chapter books) for children 12 and under. Might be suitable for some of your students in years 7—9.

OpenLibrary.Org: A comprehensive online catalogue where students can read or borrow books. You will need to show them how to use it first.

Audible: This one is free at the moment and provides access to a vast audiobook library.

Students looking for book recommendations:

For students who are looking for something new to read, the State Library of Victoria’s online community hub for teens Inside a Dog offers book recommendations and a chance to be part of an online reading and writing community.

Finally, if students find a book they love and want a suggestion for a book like it, they can use the search engine on the ‘What should I read next?’ website to generate lists of similar texts they might want to preview, or can find titles similar to popular texts on Goodreads’ ‘Read-Alikes Booklists’.

Access to short texts - fiction and nonfiction

If students need access to nonfiction texts, short stories or poetry, you can access these from the apps below. You can share texts from these sources on an online learning platform or management system with students or print and send them home:

CommonLit: You can create a free account and have access to comprehensive 7-12 resources from their digital library. These include different texts drawn from a range of genres organised by subject, topic, year level and genre, including nonfiction, short stories and poetry.

NewsELA: You can access a range of high-interest non fiction texts, including news pieces, for years 7—12. You can also adjust the Lexile levels of texts. Access is currently free.

Actively Learn: A reading platform where students can highlight, annotate, and interact with text as they read. You can share texts with individual students or with groups, complete with strategic stopping points set up throughout the text to prompt and scaffold interaction and thinking about texts. Some texts come with questions as well. The site contains a comprehensive collection of free English, Science, and History texts, including fiction and non fiction. They currently have a remote learning option available during this time. It's worth checking this one out for its vast library.

Reading Consideration #2: The ‘reading plan’

“Like successful sportspeople, successful learners create a ‘game plan’ for achieving their goals”

Okay, so students have access to texts, now what?

Like successful sportspeople, successful learners create a ‘game plan’ for achieving their goals. In this case, the goal is to read the text (well, duh!). For some of our more independent learners, this might mean that we simply step out of their way and let them read! But we know that others will need some more structure and supports to work with. Depending on your teaching context and your students, this could look like:

Protecting time to read, even during remote learning periods

Encouraging students to set aside protected time for reading in a comfortable reading spot for a minimum of 30 minutes a day. You can communicate this to parents to gain their support and check in with students via online video conferencing to monitor their reading. Here is an example of a letter to parents and carers that communicates this (inspired in part by Nancie Atwell’s parent newsletter in The Reading Zone).

Establishing a pacing guide for reading independently

Encourage students to map out what they will read and when they will read it over a period of time. This will help them determine reasonable ‘chunks’ of reading in one sitting or to set goals to read a book by a particular time. You might need to demonstrate a process for this first. To see a step-by-step guide for students and an example, click here.

Explicit teaching of reading behaviours through video or ‘one-page guides’

Teachers can demonstrate tips for staying focussed, how to maintain reading stamina and how to annotate texts. These can be shared as clear, one-page guides with photos and steps, or recorded as videos or shared through video conferencing platforms like Skype, Google Hangouts, Google Meets or Zoom.

Modelling/sharing enthusiasm for reading (remotely)

Teachers schedule time to share video of themselves giving book talks or reading/thinking aloud from enticing passages and texts relevant to students’ lives.

A low-tech alternative is to create a brief written ‘Book Talk’ structured around these three questions from Unshelved’s book review format:

Why did I pick it up?

Why did I finish it?

Who is this for?

To see/share some existing book talk videos for teens, check out:

You can also encourage students to keep a ‘Want to Read’ list of books they add to after engaging with book talks or read alouds.

Video read alouds:

Use video conferencing time for groups (or all) of your students to read excerpts of high-interest texts aloud to them, think aloud about the text, and encouraging them to respond or practice a particular reading skill.

Reading Consideration #3: Interacting meaningfully with texts

“

“The process of reading is not half asleep” (Whitman, 1898)

As English teachers, we know that to get the most out of our reading, we need to approach it by being active, thoughtful and strategic. As American poet Walt Whitman said, “the process of reading is not half asleep”! (Whitman, 1898).

So what can we do to encourage active, thoughtful and intentional reading at this time? How will we find out what’s going on in students’ minds while they read when we’re teaching remotely?

Below are a few examples of what this might look like. Whatever you choose to do, making sure that it is something that you and your students can reasonably sustain is key.

Explicit teaching of reading skills and strategies through video or ‘one-page guides’:

Teachers can model and demonstrate how to interact purposefully with texts, through annotating, tapping into prior knowledge, making connections and asking questions, to name a few. Again, these can be shared as clear, one-page guides with photos and steps, or recorded as videos or shared through video conferencing platforms like Skype, Google Hangouts, Google Meets or Zoom.

For some specific examples of how to interact with texts at the paragraph and text level, see this page of the Victorian DET Literacy Teaching Toolkit, which is open and accessible to everyone, not just Victorian teachers. You might also want to check out ‘Shared and Modelled Reading with Think Alouds’ strategy from the Toolkit here.

Creating opportunities and forums for questioning:

Encourage students to ask questions when they read can help them create meaning, deepen their understanding and develop new thinking (Harvey and Goudvis, 2017). Observing students’ creation and exploration of questions when they read is also a great way for teachers to check for understanding. Here are a few ideas:

Student-generated questions:

Encourage students to come up with their own questions to explore as they read. You might need to model how to do this first. Students can also use a Q-Chart like this one or a ‘Types of Questioning’ grid to scaffold asking questions that push deeper thinking.

In a digital learning environment, students can share their ‘best questions’ with each other on a platform like Padlet or a Google Doc and comment on them.

If students are reading a group or shared text, they can select a set number of questions they will explore as they read and submit these as formative assessment.

Using guided questioning:

Create a choice board of open-ended guided questions that students can ask themselves when reading any text.

Encourage students to strategically ‘Stop and Jot’ at regular points as they read (eg: after each paragraph or ‘chunk’ of text, at the end of each chapter, after previewing each text feature, after every few pages, etc.).

At each stopping point, encourage students to select a question to ask and explore. They can submit their questions and explorations to you as formative assessment.

In a digital learning environment, encourage students to share one question and one comment about their question on a digital platform like those mentioned above, and ask them to comment on each other’s work.

Student annotations:

You can encourage students to annotate texts purposefully and submit photographs or examples of their annotations on Padlet or Google Docs as formative assessment. A low-tech option includes taking a photo and sending it to you via their parents’ phone.

Students can record what’s confusing, what they’re wondering about, important quotations, connections they are making and other ‘tracks’ of their thinking. For an example of annotating resources from the Victorian Literacy Toolkit, see ‘Annotating Texts’ when you click here.

Graphic organisers representing student thinking:

Students can also express their thinking about reading using graphic organisers that prompt interaction with texts. These can take the form of double entry journals or four-square reflections, to name a few.

Alternatively, they could involve more visual elements, like concept mapping and flow-charting, as outlined in the Victorian Literacy Toolkit here.

Student reading responses:

You can also ask students to respond to their reading in a reader-response journal, reader’s notebook, their workbook or electronically. Students can periodically submit their responses to you.

Possibilities could include:

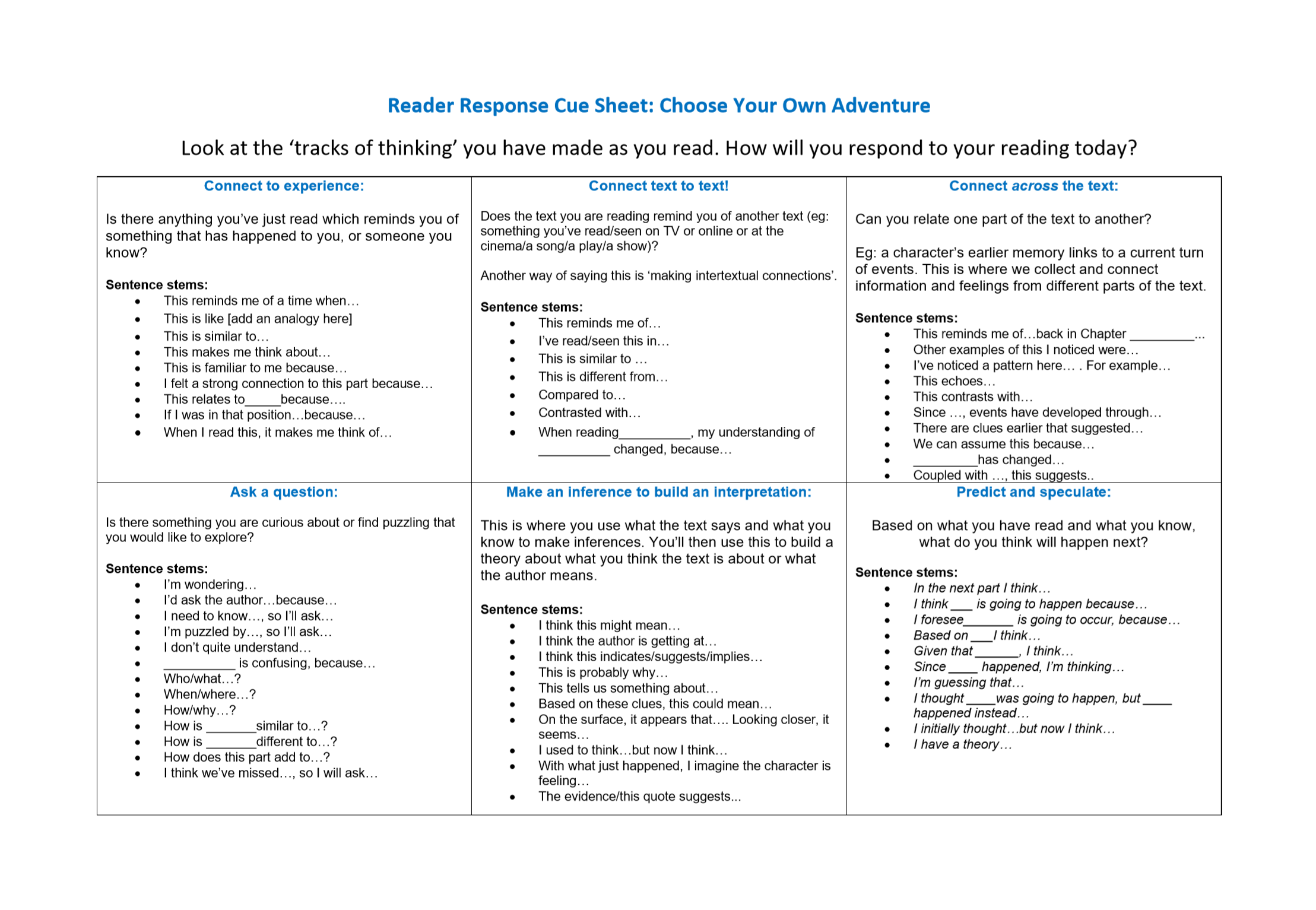

Presenting students with a choice board of ‘reader response’ options (see ‘Reader Response Cue Sheet’ below)

A ‘Track my Thinking’ form –from US teacher and writer Kelly Gallagher.

Asking students to ‘lift a line’. This is a strategy borrowed from Aimee Buckner’s book Notebook Connections which encourages students to choose a quotation from the text they are reading that resonates with them and ‘write back’ to it.

Asking students to come up with a ‘tweet’ that synthesises or challenges the core ideas of the text. Here’s one from a Literature student offering a feminist perspective of Disney’s The Little Mermaid:

Putting it all together: A Week of Reading

Below you’ll see an example of what a ‘Week of Reading’ might look like for a Year 9 English class. It’s designed to be flexible —students can engage in a video conference and be present for online minilessons, or can complete weekly formative assessments on their own and check in during individual or group video conferences and group tasks. You’ll see that I haven’t tried to bite off more than students –or I— can chew. Instead, I’ve selected a few manageable things that are purposeful, maintain a sense of routine and try to retain a sense of classroom community.

It’s also worth noting that the only reading work requiring submission includes the formative assessment checks (indicated in red) scheduled across the week. The only other requirement is that students read for 30 minutes a day.

This is basically a scaled-back, more flexible version of what would have been done in the face-to-face classroom, using remote learning tools. Having said that, weekly checks for understanding are intended to guide adjustments or further ‘paring back’ of the learning plan, depending on where students are at:

At the end of the day, you know your students and their strengths, struggles and idiosyncrasies. What is most relevant and meaningful for them at this time?

What are your ideas for encouraging student reading in a remote learning context? Feel free to comment and share below!

References:

Anderson, R. Wilson, P. and Fielding, L. (1988). ‘Growth in Reading and How Children Spend Their Time Outside of School’, Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 285—303.

Atwell, N. (2007). The Reading Zone. New York: Scholastic.

Cunningham, A.E. (2005),’Vocabulary Growth Through Independent Reading and Reading Aloud to Children’ in Hiebert, E.H. and Kamil, M.L. Teaching and Learning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice. London: Routledge, pp. 45-69.

Guthrie, J. T., and V. Greaney. 1991. ‘Literacy Acts’ in Handbook of Reading Research. vol. II. Edited by R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, and P. D. Pearson. New York: Longman.

Krashen, S.D. (2004). The Power of Reading: Insights from the Research (2nd Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Moss, B. and Young, T.A. (2010). Creating Lifelong Readers Through Independent Reading. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Miller, D. and Moss, B. (2012). No More Independent Reading Without Support. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Stanovitch, K.E. (1986). ‘The Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences for Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy.’ Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 21, pp. 360-407.

Stanovich, K.E. and Cunningham, A.E. (1993). ‘Where Does Knowledge Come From? Specific Associations Between Print Exposure and Information Acquisition’, Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 211-229.

Whitman, W. in Lovell Triggs, O. and Whitman, W. (1898), Selections from the Prose and Poetry of Walt Whitman. Scanned copy from Cornell University Print Collections (Available June 25, 2009).

[i] Moss and Young, 2010; Miller and Moss, 2012; Anderson, Wilson, and Fielding, 1988; Guthrie and Greaney, 1991; Krashen 2004; Cunningham and Stanovich, 1991; Stanovich, 1986.