After a short break: Four ways of activating and building knowledge at the start of a new term

By Nicole Marie and Judy Douglas

You probably know the feeling. You’ve greeted your students at the door, listened as they’ve shared their holiday stories, and have set the scene for the new learning of the day (or unit!). Now it’s time to re-energise, pick up where you left off, and create a jumping-off point into new thinking territory. As soon as you pose a question, though, you know something’s off. You hear crickets. So you switch tactics and say something like, ‘You remember last term, when we…’ . But still, those crickets! You feel the urge to resort to ‘telling’ over teaching, because part of you believes it’ll just be quicker, and they should know this, anyway. But another part of you recognises that this isn’t the best (or the most stimulating!) practice, and that if you go down this path, all you’ll be doing is reciting your own prior knowledge, rather than engaging students to interact with what they already know and in turn, providing you with vital information you can use to target your teaching.

The above scenario is all too familiar. It’s common to come back from a break with a slight case of ‘holiday amnesia’, for teachers and students alike! Just like we teachers need to review where we are at and where we are going at the start of a new term, students need a chance to not only acclimate themselves back into the classroom, but to ‘rehearse’ what they already know in meaningful ways and to connect this to the new. Why? When it comes to reviewing prior learning, research shows that we forget information that we don’t initially store successfully in a meaningful mental model, or that which we do not retrieve often enough (Sherrington, 2019: 11-12). What’s more, research also tells us that it’s easier to learn something new when “composed of familiar elements” (i.e: when we connect it to what we already know) (Reder et al, 2016). In other words, when we have not had regular opportunities to think, discuss and write about what we have learnt in ways that are meaningful to us or which connect to what we already know, then what we’ve learnt won’t stick. It’s no wonder that ‘holiday amnesia’ is so common!

With this in mind, this post will explore four ways to help activate and build knowledge at the start of a new term after a holiday break, which are designed to:

get students curious and interested in their learning to ensure meaningful connections

encourage students to connect the known to the new

be open-ended enough to provide plenty of room for students to rehearse and show what they know

elicit information about student learning to inform next steps (Wiliam, 2017)

1. Thinking routines involving personal reflection

One way of making the ‘jumping off’ point into new or deeper learning more accessible for students is to engage them in a thinking routine —an explicit series of steps that guide thinking—followed by a clear link to new learning.

Ensuring the thinking routine involves personal reflection increases the likelihood that the students’ interaction with the learning will be more meaningful, and therefore more memorable.

What this might look like:

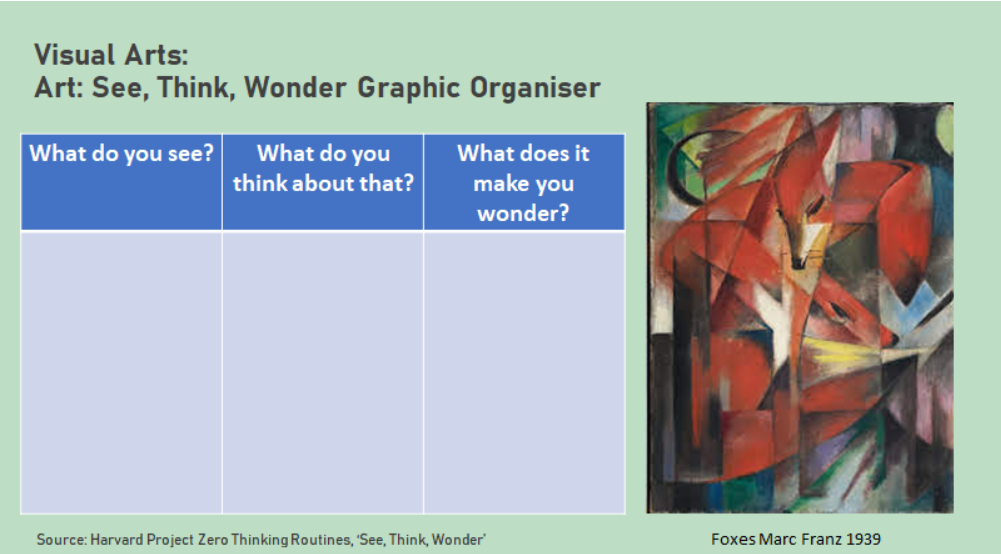

See, Think, Wonder:

A simple, versatile thinking routine that stimulates curiosity through close observation is Harvard Project Zero’s ‘See, Think, Wonder’ routine. First, this involves presenting students with stimulus material (an image, artwork, screenshot, artefact, demonstration, quotation, etc.). Students are then asked to jot down responses to the following three questions about the stimulus material:

1. What do you see? (“I see…”)

2. What do you think about that? (“I think…”)

3. What does it make you wonder? (“I wonder…”)

Finally, students can be invited to share their responses, which can be listed and recorded so all students can see. Student ‘wonderings’ can be used as a ‘jumping off point’ into deeper discussions about the concepts being learned, and can be used to drive deeper learning that has intrinsic purpose. These can be returned to at different points in a sequence of learning.

For some Science and Art classroom examples, see the images below:

‘Triple H’ Routine:

Another example of using thinking routines involving personal reflection is to invite students to participate in a ‘Triple H’ personal reflection, before asking them to apply this thinking to a character in a text they are reading. First, students are asked to jot down some thinking about important events in their lives that best engage in these three prompts:

Nominate a hero in your life and explain why they are your hero (eg: someone who has inspired you or encouraged you to achieve something.)

Share your thinking about a highlight in your life so far and its impact on you (a big achievement, enjoyable experience, learning experience, holiday, etc.)

Identify a hardship you have experienced and its impact on you (an experience that you have found hard which you are comfortable writing about)

If discussing hardship is triggering for students, you might adapt this activity or ask students to give examples of hardships that they have successfully worked through (eg: transition to high school, etc.)

Next, students can share their thinking with a partner they are comfortable with (this has the added benefit of building classroom trust).

Following this, ask students to apply the ‘hero/highlight/hardship’ reflection to a character in the text they are reading:

Who do you think your character’s ‘hero’ is/would be and why? This can be something the author has directly stated or it could be your own thinking based on what you know about the character.

Think about your character’s journey. What is a ‘highlight’ event for your character and what impact did it have on them?

Think about what has been challenging for your character. What hardships has your character faced and what happened as a result?

While ‘Triple H’ reflections are usually used by coaches and facilitators to create trust in group situations (it was even used by Richmond Football Club), in this scenario, they are used to build character empathy.

What, Who, How, Now:

One more example is a ‘What, Who, How, Now’ personal scenario and routine, which can be used to stimulate students’ thinking about objects related to what they’re learning about (eg: historical artefacts, scientific or mathematical materials or equipment, symbols from the text students are reading, artworks, etc.). Students are given a scenario (Eg: “You are…”), presented with the object, and are then asked to engage in the following types of questions, depending on the object under question:

‘What’ questions: What could it be?

‘Who’ questions: Who do you think it belongs to/who might use this/who

‘How’ questions: How might this have been used? How might this play an important part in [the character’s journey/the demonstration/the experiment, etc]?

Questions that link to ‘Now’: How might we use this today? How might this be relevant to what we are learning about? How might this connect to [insert concept or topic here]?

For a History classroom example, see below:

You can find a range of thinking routines to suit any purpose within Harvard Project Zero’s Thinking Routines Toolbox.

2. ‘Taking a stand’ on issues relevant to students’ learning and their lives, with opportunities to generate questions and revise their thinking

Inviting students to share and then justify their opinions about issues relevant to their learning not only provides opportunities for stimulating student engagement and connecting learning to students’ lives, but for eliciting how well students can explain their thinking about what they are learning. This can help provide vital information for teachers to shape the next steps of instruction.

As they learn more and more about particular concepts, students can revisit their initial opinions to see if their thinking has changed. After sharing their opinions, it might also be worth inviting students to pose questions about the issues relevant to learning to develop an intrinsic sense of purpose to drive future learning.

What this might look like:

Taking a position:

This could involve generating a series of provocations or statements about what students are learning/about to learn. It’s important that these statements or provocations are framed as being relevant to students’ lives. Students are then invited to share their position on each statement by walking to designated parts of the room. Students can then be asked to justify their thinking (eg: “What makes you say that?”, “Why do you think...?”). They can also ‘cross the room’ to change their mind if they hear something convincing from a peer.

Variations of this type of activity include: four-corner debates, agree/disagree continuums, Philosophical Chairs and Anticipation Guides.

Afterwards, students can generate questions about the issues which can drive deeper learning, and can be invited to reflect upon whether their original thinking has been confirmed, challenged, or has changed.

In a Year 10 English class, for example, students were presented with a series of statements related to a novel they were about to study, framed in ways that were relevant to students’ lives or piqued student interest. Eg: “Growing up happens the moment you realise the adults in your life are not perfect”, “History is always written by the winners”, “We must tell the truth even when it might hurt people”, “Prejudice is part of human nature and there’s nothing we can do about it”, “What is ‘right’ behaviour and what is ‘wrong’ behaviour is always clear”, etc. Students were then asked to ‘take a stand’ and justify their thinking through participating in an agree/disagree continuum activity. Afterwards, it was explained to students that the ‘real life’ issues they discussed would be addressed in the text they were reading. Students were invited to generate questions about these issues that could help add purpose to their reading, which were recorded and displayed on the walls. Some examples of their questions included:

Which characters might struggle with truth-telling and why?

How do different characters define what’s ‘right’ and what’s ‘wrong’ behaviour? What happens after?

What growing up experiences will we see in this novel? What causes them? How do they play out?

Throughout the unit, students will engage with the questions they generated. They will also be asked to revise their thinking about the provocative statements with new information gathered and interpretations formed as they read.

Ranking activities:

In small groups, students can be asked to rank a series of items related to what they are learning/will learn (eg: statements, events, quotations, images, etc.) on a scale. The scale can be organised in terms of significance (most important to least important), effectiveness (most effective to least effective), scope of impact (most consequential to least consequential) or any other measure relevant to what students are studying. Groups can then share and justify their thinking with the class. A variation of this is a diamond ranking activity. Students can return to this and revise their thinking as they learn more.

3. Anticipation and review activities

Anticipation and review activities ‘wake brains up’ and stimulate students’ curiosity about what they will be learning next. They involve students making predictions about what they’ll be learning, followed by developing a strong sense of purpose for finding out more. The ‘review’ part of these activities involves students retrieving what they know, delving more deeply into learning and revising their initial thinking, building on what they know. When designed carefully, these kinds of activities are accessible ‘jumping off’ points into deeper learning.

Some examples include:

Mind’s Eye strategy:

The teacher selects a series of important vocabulary words relevant to what students will be learning or a text they will be reading (anywhere between 8 and 30 words, depending on your purpose and students). Next, the teacher reads the words out loud to students, pausing in between. Students are asked to form mental images (i.e: what they ‘see’ in their ‘mind’s eye’) and to then predict what they will be learning or reading about. Jennifer Gonzales, the woman behind the Cult of Pedagogy blog, describes this activity as a useful pre-reading strategy, which “grabs students' attention before they ever read a single word and creates a mystery that can only be solved by reading the text.” Click on the link in the sub-heading or the video below for more detail (both from Cult of Pedagogy).

Anticipation Guide:

Before learning something new or reading a text, students respond to a series of statements about the key concepts or issues they will be interacting with, indicating agreement or disagreement. In this way, they reveal their preconceived, initial ideas or misconceptions. They then read and learn more about a topic to see if their initial thinking is confirmed, challenged or changed in any way. Click the link in the sub-heading for more information.

Probable Passage:

The teacher selects 8-15 important words and concepts from a text that students will be reading, which is related to what they are/will be learning. Students categorise the words using the text structure or elements of narrative (outlined to students beforehand), and then summarise what the passage might be about. They then read passage to determine if their predictions were correct, and add any missing information to their summaries in a different colour. For an example of how to use it with a fiction text, click here. For a more versatile example that can be used with fiction or nonfiction texts, click here.

Postcards:

Place a series of at least 6 enlarged pictures or quotations on tables intended for small groups, or up around the room. These are your ‘postcards’. Ensure that what’s on the postcards is relevant to what students will be learning about. The connection to learning can be explicit (in the case of quotations) or more symbolic (icons representing different emotions, for example). Next, pose a question that invites students to choose one postcard, link it to what they are learning about and to justify their choice. If students are working in groups, they can select a postcard of their own. If you have placed the postcards on the walls around the room, ask students to walk to that section of the room to indicate their choice.

Eg: “Choose a postcard that represents how confident you feel about ________”

“Choose a postcard that represents an important idea to do with_______”

“Choose three postcards that captures what you think we’ll be learning about and doing when we explore _________”

“Choose two postcards that best represent what you know about _________”

“Which of the six postcards best captures what Stanley was like at the beginning of the story?”

ABC Lists:

Students write out the alphabet from A to Z and leave spaces next to each letter. Nominate a topic or concept you would like students to share their knowledge about (eg: ‘Film Language’, ‘Space’, ‘The characters in [text]’, ‘The French Revolution’, ‘The Musculoskeletal System’, ‘Medieval Japan’, ‘Contemporary Art’, ‘Occupational Health and Safety’, etc.) They are given a set amount of time (5-10 minutes) to brainstorm as many words to do with that particular topic, either individually or in groups. Their aim is to think of as many relevant words as possible and to see if they can think of a word for each letter of the alphabet. Students can then share their responses and add new words to their lists in a different colour. They can draw dotted lines between words that are connected. Students’ responses can be recorded and shared as a ‘Word Wall’. See the Year 9 Media example below:

For some review and knowledge building strategies, including see the examples in Chapter 2 of ReLeah Cossett Lent’s book Overcoming Textbook Fatigue: 21st Century Tools to Revitalize Teaching Learning, available here.

4. Vocabulary exploration:

In a vocabulary exploration students are given time to develop a deeper understanding of key words and concepts that they both already know and will ‘need to know.’ It also helps us evaluate our students’ current understanding of these concepts, and sets them up for future learning. By using a variety of low-stakes strategies that encourage curiosity about the words and concepts, we can make the learning engaging and interesting.

What this might look like:

Student-created definitions:

We can start with students creating their own definitions of words and concepts by synthesising the definitions provided by different dictionaries; identifying patterns or similarities in the words used in these definitions. Students can then use these words to formulate their own definitions in their own words.

Using non-examples:

Using non-examples helps students to further define a word or concept and to specify its meaning. A non-example is a definition or explanation of a word that is ‘not quite right’, rather than a totally unrelated or opposite word. An example of how we can engage students with non-examples is by presenting a list of definitions or explanations that are ‘true’ examples and non-examples, then asking students to identify which are ‘true’ and which are non-examples. Having students think independently, sharing with a partner, discussing (debating) as a group, and then sharing their thinking as a whole class means students are meaningfully interacting with the words and continuing to build a deep understanding of not just the definition, but accurate use of the word. Additionally, we can get students to develop their own lists and challenge other students to decide on the words that represent examples and non-examples, encouraging them to justify their responses. For an example that could be used in a Maths classroom, see the image below:

‘Closest synonyms’:

We can begin to connect students’ knowledge of a word or concept with the topic they are learning about by building lists of ‘closest synonyms.’ Students determine, from a list of synonyms of a word, the ones that are closest or most relevant to how they would use it in a topic, subject, or context. For example, students can select synonyms for the word ‘development’ that would most closely relate to ‘character development.’ They might also identify the closest synonyms for ‘development’ that relate to discussing plot or structure of a text. This activity opens up lots of opportunities for collaboration, discussion and debate as they share, refine, and determine the ‘best’ synonyms and create word walls or lists they can refer to. It also creates opportunities for discussing how they will use the words in a unit of study.

Encouraging students to investigate and use the words:

Finally, we can give students the space to explore or investigate and use the words. This could be through a Quickwrite —a low-stakes, nonstop writing activity —prompted by a word or concept. Students might also create visual representations, or find ways to use the words in their own world (e.g. where in their life would the word ‘development’ be apt). As long as students are finding ways to interact with the words, we are in a position where we can build deeper understanding.

What are your ‘go-tos’ for eliciting and building student knowledge at the start of a new term?

References:

Reder, L., Liu, X.L., Keinath, A., Popov, V. (2016). ‘Building knowledge requires bricks, not sand: The critical role of familiar constituents in learning’, Psychonomic Bulletin Review: 23, 271--277. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758%2Fs13423-015-0889-1.

Sherrington, T. (2019). Rosenshine’s Principles in Action. John Catt Educational: Melton, Woodridge.

Wiliam, D. (2017). Embedded Formative Assessment, 2nd Ed. Solution Tree Press: Bloomington, IN.